I went through a Gwyneth Jones phase when the Aleutian Trilogy was being published by Tor. Dave Hartwell was her editor at Tor, and I used to talk about her books with him. I went back and read all of her adult SF and fantasy, starting with

Escape Plans, and I read one Ann Halam YA book too. My favorites were

Divine Endurance,

White Queen, and

North Wind. In her I found an heir, both literary and feminist, to Joanna Russ. I found the third book in the Aleutian Trilogy,

Phoenix Cafe, a big disappointment, and between that and the fact that Tor dropped her after that, I lost track of her career.

On my TAFF trip in 2003, however, I did manage to pick up a British paperback of her next novel,

Bold As Love, which I'd heard her read from when she taught at Clarion West in 1999. (I wouldn't have remembered that date, except she mentions it in the acknowledgements to the novel, where, alas, she also refers to the Crocodile Club, which is actually called the Crocodile Cafe. Ah well, a very minor error in the grand scheme of things.) So as part of my ongoing project of reading mostly books by women, I finally pulled it off the Pile a couple of weeks ago. Alas, I found it completely impenetrable -- which was also true of her first two novels, now that I think of it. I didn't care about the characters and couldn't keep some of them straight, I couldn't figure out the political factions, I couldn't distinguish the different bands or which characters were in which band. In short, I found it completely incomprehensible. On the off chance that it was the chemo causing the confusion, I consulted with the temporarily-retired

![[livejournal.com profile]](https://www.dreamwidth.org/img/external/lj-userinfo.gif) fishlifter

fishlifter, who I knew had had some problems with the book too, and she confirmed that she had had many of the same problems I was having. Worse, she told me it was the first in a five book series, not the diptych I expected. I gave up on it at the point.

I was considering the semi-retired

![[livejournal.com profile]](https://www.dreamwidth.org/img/external/lj-userinfo.gif) fishlifter

fishlifter's recommendation of another novel by Jones called

Spirit when I recalled that I had one of Jones' non-fiction books on my Pile. Since I'd been vaguely feeling that I've been reading way too much fiction lately anyway, I started reading

Imagination/Space: Essays and Talks on Fiction, Feminism, Technology, and Politics, which was published by Aqueduct Press out of Seattle. Two days later, I had read the whole thing. Although I had read some of the excellent reviews and essays on her website during my period of infatuation with her writing, I hadn't heard that in 2008 she had won a well-deserved Pilgrim Award for Lifetime Achievement in the field of science fiction scholarship. She turned out to be an heir to Joanna Russ as an incisive critic and reviewer as well as an author of self-critical feminist science fiction.

However, at first it seemed like a bad sign when the first essay in the book -- "What Is Science Fiction?" quoted extensively from the book I'd just bounced off of,

Bold As Love. But I admired the essay greatly for not trying to pin the origins of SF to one book or one literary movement. Instead she cites multiple roots in the Gothic (expecially Shelley's

Frankenstein and Stoker's

Dracula), travel writing of the ancient past (e.g. Herodotus), the Romantic concept of the Sublime (citing Burke's essay on the subject), and the more modernist genre of the Grotesque (e.g. Kafka's "Metamorphosis"). I love this kind of genealogical, very literate, influence-spotting approach to genre history, so this was a perfect essay for me.

Another favorite piece was "Postcript to the Fairytale", subtitled "A Review of

The Two of Them by Joanna Russ." This is one of Russ's most slippery, shifting, difficult works of fiction, and Jones does a brilliant job of tracing Russ's wrestling match with the contradictions of exercising power as a woman in a patriarchal society and her resistance to the common feminist urge to retreat into fantasies of female superiority. Like Russ, Jones is not much for the easy answer, and she is as pointed and balanced in her criticism of feminists as she is of sexists. Of course

The Two of Them is partly about the ways women are complicit in their own oppression. Jones sees her own complicity too in brilliant passages like this:

The story behind the fiction, the story of a generation, always starts the same way: I was a girl-child in the fifties. I was attracted to the alien culture (indubitably alien!) of a set of books with rockets on the spines. Maybe I was influenced, though I didn't really know it, by my mother's memories of the halcyon days of World War, when women's work was needed outside the home and she had a life. Maybe I felt her unease, though she never talked about it, at being socially engineered back into the kitchen and the negligee. (Maybe I called this "not wanting to be like my mother.") The books were exciting and adventurous, and there were plenty of tomboy girl characters. I didn't know they were there for decoration, I thought it meant the genre had a place for me! So I ran away with Science Fiction, to start a new life. And here I am, still happy to be dressed in long underwear, with my raygun, but sorely disillusioned about those tomboys ... And then the story divides. The unregenerate tomboys keep their rayguns; the alpha female fans create a female, womb-friendly space within sf; but aren't both playing by the rules of the boy club? The Two of Them examines this dilemma, with illustrations. (p.48)

Jones is frequently provocative. Her essay about the links between horror, sexual arousal, and science fiction is called "String of Pearls," which although derived from a work of criticism, it is a work of criticism about pornography, which leaves the sexual suggestion intact. Her essay on video games connects that industry to the science fiction field in ways that I haven't seen anyone else talk about, although that likely reflects my own lack of interest in video games. She provides fascinating insight into her own working methods as a writer, specifically in "True Life Science Fiction: Sexual Politics and the Lab Procedural" about tagging after a female molecular biologist, Dr Jane Davies, while researching her novel

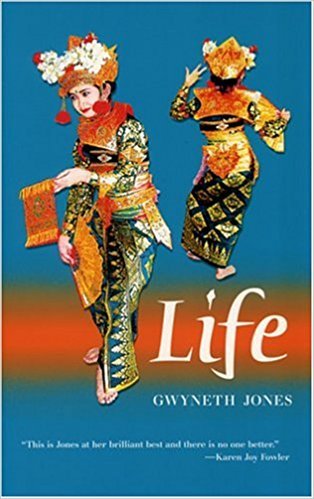

Life, which is about a non-Darwinist concept of evolution.

As with any good work of criticism, I come away from it with a list of other books I now want to read. Jones provides not one but two lists of top feminist science fiction, and I've already started reading Joan Sloncewski's

A Door into Ocean, which she mentions more than once, not necessarily disparagingly, as an example of "a female, womb-friendly space within sf" and has long been on my big list of books I'm interested in, largely due to the advocacy of a feminist writer-friend of mine. Indeed Jones'

Life now seems like the next novel of hers I want to try, but based on this collection I'd also like to track down her previous non-fiction collection,

Deconstructing the Starships. I thought

Imagination/Space was completely fascinating and riveting, and I'd like to read more of the same.

I first encountered the fiction of Gwyneth Jones when her novel White Queen was published in the US in 1991. I immediately felt I'd discovered the heir to Joanna Russ and went back and read what I thought were her earliest novels, starting with Divine Endurance, although I see that Wikipedia now list four earlier novels. Her American editor was David Hartwell, and we discussed the rest of the Aleutian Trilogy, which started with White Queen, as it came out. Something about the third book, The Phoenix Cafe, with it's cavalier attitude toward men as an eternal danger to women and children, really put me off, however, and I gave up on Jones after that, although I was still curious enough about her to pick up the first book of her next series, Bold As Love at the Eastercon on my TAFF trip in 2003. I don't think it ever had a US publisher, nor did the rest of that series. I took it off my To Be Read pile not long ago, and bounced off what I found to be a very confusing story about European politics (seemingly very prescient in the post-Brexit world) and countercultural defiance. I switched to another book of hers in the Pile,

I first encountered the fiction of Gwyneth Jones when her novel White Queen was published in the US in 1991. I immediately felt I'd discovered the heir to Joanna Russ and went back and read what I thought were her earliest novels, starting with Divine Endurance, although I see that Wikipedia now list four earlier novels. Her American editor was David Hartwell, and we discussed the rest of the Aleutian Trilogy, which started with White Queen, as it came out. Something about the third book, The Phoenix Cafe, with it's cavalier attitude toward men as an eternal danger to women and children, really put me off, however, and I gave up on Jones after that, although I was still curious enough about her to pick up the first book of her next series, Bold As Love at the Eastercon on my TAFF trip in 2003. I don't think it ever had a US publisher, nor did the rest of that series. I took it off my To Be Read pile not long ago, and bounced off what I found to be a very confusing story about European politics (seemingly very prescient in the post-Brexit world) and countercultural defiance. I switched to another book of hers in the Pile,  I read Synners not long after it was published in 1991, but I don't remember what I thought of it. I liked it a lot the second time. It's a novel full of furious energy and lots of ideas. What surprised me a little bit was how much it's about a counterculture, but also how realistically the countercultural life is depicted. At time it reminded me of Delany's Dhalgren on that front, with free spirits squatting in utter squalor, eating badly in filthy surroundings. It's not a very romanticized portrait.

I read Synners not long after it was published in 1991, but I don't remember what I thought of it. I liked it a lot the second time. It's a novel full of furious energy and lots of ideas. What surprised me a little bit was how much it's about a counterculture, but also how realistically the countercultural life is depicted. At time it reminded me of Delany's Dhalgren on that front, with free spirits squatting in utter squalor, eating badly in filthy surroundings. It's not a very romanticized portrait.

I don't find this novel in my book log, which I started in March 1979, which is kind of remarkable. It implies that I had already read it by that time, which is logistically possible because the hardcover was published in March 1978. But I couldn't afford hardcovers back then, so I either got it through the SF Book Club (May 1978) or borrowed it from a friend. The paperback didn't come out until June 1979. I read McIntyre's first novel, The Exile Waiting, in July 1979, and I'm pretty sure I read those two novels out of order. I don't remember for sure, but I probably met Vonda when I came to Seattle for Norwescon in March 1979, so it's interesting to consider that I had probably already read something by her by then.

I don't find this novel in my book log, which I started in March 1979, which is kind of remarkable. It implies that I had already read it by that time, which is logistically possible because the hardcover was published in March 1978. But I couldn't afford hardcovers back then, so I either got it through the SF Book Club (May 1978) or borrowed it from a friend. The paperback didn't come out until June 1979. I read McIntyre's first novel, The Exile Waiting, in July 1979, and I'm pretty sure I read those two novels out of order. I don't remember for sure, but I probably met Vonda when I came to Seattle for Norwescon in March 1979, so it's interesting to consider that I had probably already read something by her by then. This book was recommended to me by

This book was recommended to me by  I had to look it up in my book log (fortunately it was near the beginning), but it turns out I read this novel before I read any of Tiptree's short stories. It appears that I read it when the paperback came out in 1979. This time I read the first edition hardcover that I picked up used somewhere along the way. (Published by G.P. Putnam's Sons! Boy, that was a different era of publishing, wasn't it?) So it's funny that my memory was that I was disappointed by the novel. Apparently I wasn't disappointed because it wasn't as good as her short fiction but because I didn't think it worked as a novel.

I had to look it up in my book log (fortunately it was near the beginning), but it turns out I read this novel before I read any of Tiptree's short stories. It appears that I read it when the paperback came out in 1979. This time I read the first edition hardcover that I picked up used somewhere along the way. (Published by G.P. Putnam's Sons! Boy, that was a different era of publishing, wasn't it?) So it's funny that my memory was that I was disappointed by the novel. Apparently I wasn't disappointed because it wasn't as good as her short fiction but because I didn't think it worked as a novel. Gwyneth Jones writes about this book a number of times in her collection,

Gwyneth Jones writes about this book a number of times in her collection,  I went through a Gwyneth Jones phase when the Aleutian Trilogy was being published by Tor. Dave Hartwell was her editor at Tor, and I used to talk about her books with him. I went back and read all of her adult SF and fantasy, starting with Escape Plans, and I read one Ann Halam YA book too. My favorites were Divine Endurance, White Queen, and North Wind. In her I found an heir, both literary and feminist, to Joanna Russ. I found the third book in the Aleutian Trilogy, Phoenix Cafe, a big disappointment, and between that and the fact that Tor dropped her after that, I lost track of her career.

I went through a Gwyneth Jones phase when the Aleutian Trilogy was being published by Tor. Dave Hartwell was her editor at Tor, and I used to talk about her books with him. I went back and read all of her adult SF and fantasy, starting with Escape Plans, and I read one Ann Halam YA book too. My favorites were Divine Endurance, White Queen, and North Wind. In her I found an heir, both literary and feminist, to Joanna Russ. I found the third book in the Aleutian Trilogy, Phoenix Cafe, a big disappointment, and between that and the fact that Tor dropped her after that, I lost track of her career.  I guess I'm done with crime novels about psychologically bizarre characters, so I'm not going to read the last two novels in the Library of America's Women Crime Writers of the '40s and '50s omnibus. I got one chapter into Margaret Millar's Beast in View and thought, "I can't take any more mental illness!"

I guess I'm done with crime novels about psychologically bizarre characters, so I'm not going to read the last two novels in the Library of America's Women Crime Writers of the '40s and '50s omnibus. I got one chapter into Margaret Millar's Beast in View and thought, "I can't take any more mental illness!" I've long been interested in Patricia Highsmith, largely because of the number of films based on her books, including the excellent Carol (based on Highsmith's The Price of Salt.) Now that I've read one of her crime thrillers, however, I'm not sure I'm going to like her books. The Blunderer was her third published novel -- a crime novel about three repulsive characters being cruel to each other. I admit the structure is quite interesting, but I found the execution a little repetitious.

I've long been interested in Patricia Highsmith, largely because of the number of films based on her books, including the excellent Carol (based on Highsmith's The Price of Salt.) Now that I've read one of her crime thrillers, however, I'm not sure I'm going to like her books. The Blunderer was her third published novel -- a crime novel about three repulsive characters being cruel to each other. I admit the structure is quite interesting, but I found the execution a little repetitious.  The Blank Wall is a 1947 crime novel that's been adapted to film twice: once as a film noir called The Reckless Moment (1950) and the other a contemporary thriller (that is, set in the present day of 2001) called The Deep End. The basic scenario in all three versions of the story is a suburban mother trying to hold the family together while her husband is away at war. Her underage daughter becomes enamored of a sleazy crook who wants to blackmail her, and the mother is sucked into a criminal underworld that is completely outside her mundane experience as a home-maker. (In The Deep End, the gender of the child who is imperiled is changed from female to male, and the son is gay.) I don't believe it's a major spoiler to say that the sleazebag is accidentally murdered, and the mother gets involved in covering up the murder only to have another blackmailer show up with letters her daughter wrote to her exploiter/boyfriend, which he threatens to send to the newspapers unless the mother pays him five thousand dollars.

The Blank Wall is a 1947 crime novel that's been adapted to film twice: once as a film noir called The Reckless Moment (1950) and the other a contemporary thriller (that is, set in the present day of 2001) called The Deep End. The basic scenario in all three versions of the story is a suburban mother trying to hold the family together while her husband is away at war. Her underage daughter becomes enamored of a sleazy crook who wants to blackmail her, and the mother is sucked into a criminal underworld that is completely outside her mundane experience as a home-maker. (In The Deep End, the gender of the child who is imperiled is changed from female to male, and the son is gay.) I don't believe it's a major spoiler to say that the sleazebag is accidentally murdered, and the mother gets involved in covering up the murder only to have another blackmailer show up with letters her daughter wrote to her exploiter/boyfriend, which he threatens to send to the newspapers unless the mother pays him five thousand dollars. SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS

SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS I read this novel after a discussion on Facebook when I posted a picture of an Aminita muscaria mushroom and Rich Coad quoted the opening of We Have Always Lived in the Castle:

I read this novel after a discussion on Facebook when I posted a picture of an Aminita muscaria mushroom and Rich Coad quoted the opening of We Have Always Lived in the Castle: This is the second novel in the Library of America's Women Crime Writers of the 1940s and '50s.

This is the second novel in the Library of America's Women Crime Writers of the 1940s and '50s.  THERE ARE SPOILERS.

THERE ARE SPOILERS. I'm starting to think I should just read Andre Norton novels for the rest of my chemotherapy, because I'm finding complex, ambitious novels like this one difficult to parse in my current mentally-lethargic state. There are a lot of characters, a lot of locations, and a lot of story thrown at us in short bursts that form a kind of shifting mosaic. It's dazzling, but I tended to lose my way at times.

I'm starting to think I should just read Andre Norton novels for the rest of my chemotherapy, because I'm finding complex, ambitious novels like this one difficult to parse in my current mentally-lethargic state. There are a lot of characters, a lot of locations, and a lot of story thrown at us in short bursts that form a kind of shifting mosaic. It's dazzling, but I tended to lose my way at times. Labeled "A Memoir" on the jacket, this book is actually trying to do a lot of different things. The subtitle is "The Story of a Marriage, a Family, and the Quest for Life." In the blurbs, Judy Woodruff is quoted: "This extraordinary, memorable look inside the life of a loving family facing a terrible diagnosis raises urgent questions all of us need answered about the delivery and cost of medical care in our country." This book was given to me by my brother months ago, and now that I've read it I'll be curious to find out what he took from it, because I had a hard time with it.

Labeled "A Memoir" on the jacket, this book is actually trying to do a lot of different things. The subtitle is "The Story of a Marriage, a Family, and the Quest for Life." In the blurbs, Judy Woodruff is quoted: "This extraordinary, memorable look inside the life of a loving family facing a terrible diagnosis raises urgent questions all of us need answered about the delivery and cost of medical care in our country." This book was given to me by my brother months ago, and now that I've read it I'll be curious to find out what he took from it, because I had a hard time with it. Lucy Sussex is an Australian writer whom I've actually met. In fact, she gave me the copy of this collection of short fiction when Sharee and I visited her and her partner, Julian Warner, at their Melbourne home just over a decade ago. I've run into her socially in Seattle at least once since then, too.

Lucy Sussex is an Australian writer whom I've actually met. In fact, she gave me the copy of this collection of short fiction when Sharee and I visited her and her partner, Julian Warner, at their Melbourne home just over a decade ago. I've run into her socially in Seattle at least once since then, too. Back in March I read Pym's

Back in March I read Pym's